Single-use plastic is a worldwide issue. More than 300 million tons of plastic waste are generated globally each year, with roughly half designed to be used once and discarded. Despite decades of awareness, only a small fraction of plastic is ever recycled. The rest ends up in landfills and ecosystems, breaking down slowly into microplastics that can persist for generations.

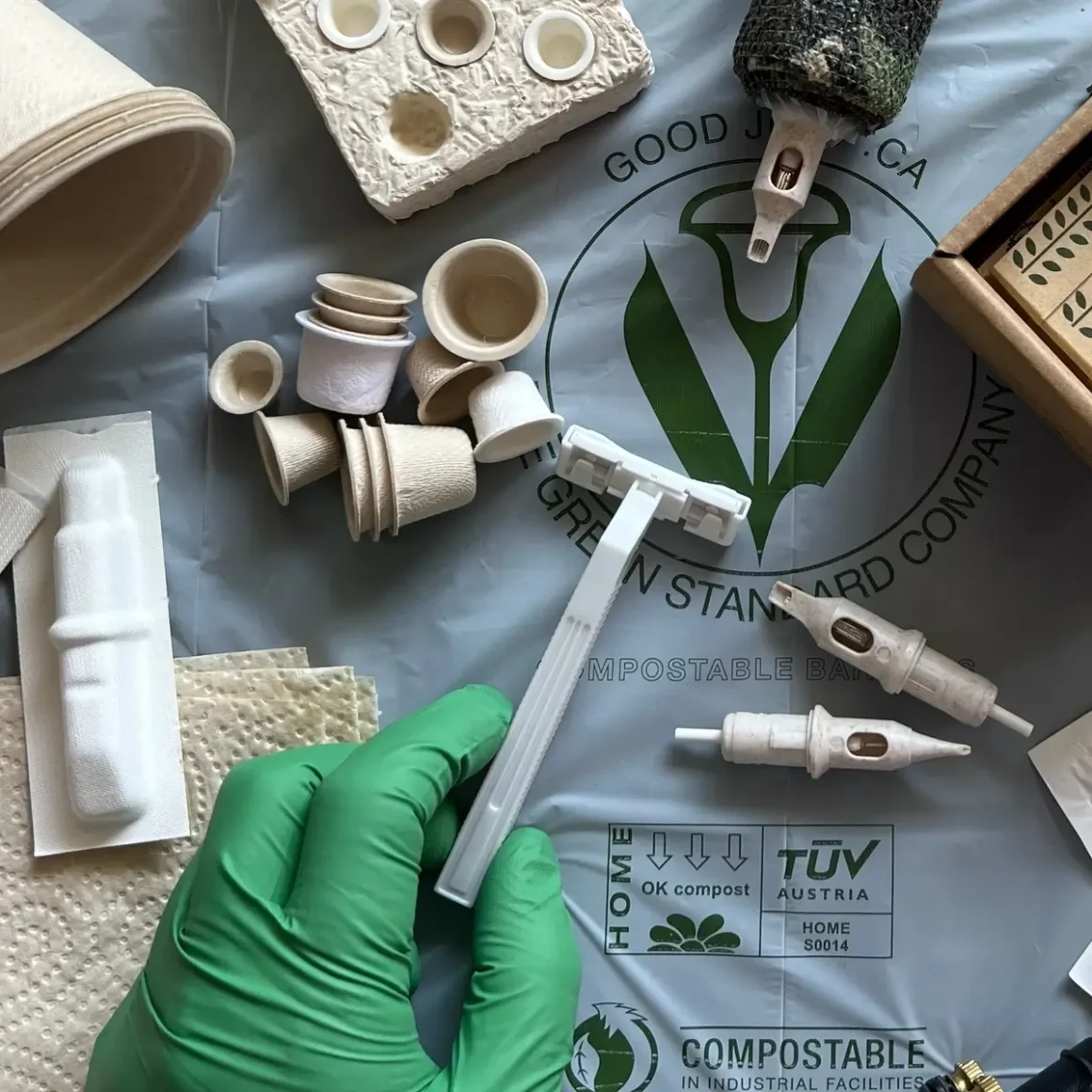

This reality spans industries from food service and fashion to healthcare and manufacturing. Tattooing exists inside that same system. While it is not a major global polluter by volume, it is a trade built on disposables for a reason. Bloodborne pathogen standards, cross-contamination prevention, and client safety require many materials to be single-use. Gloves, ink caps, rinse cups, station covers, clip cord sleeves, machine bags, and protective films are discarded after every client as part of responsible practice.

For most artists, this waste has long been accepted as unavoidable.

For Lee, a tattoo artist, shop owner, and longtime activist, it became harder to ignore.

“It was a small tattoo, maybe three inches,” Lee recalls of a session in 2018. “When we finished, my client looked at the tray and said, ‘That’s a lot of plastic garbage for such a small piece.’ The way they said it so plainly just stuck with me.”

Anyone who tattoos recognizes that moment. Tear-down is muscle memory. Barriers get rolled, ink caps dumped, gloves peeled off, everything bundled up and dropped into the bin. You close the lid and reset for the next client. It’s routine. But after that comment, the routine carried a different weight.

The issue was never safety. Tattooing has hard rules for a reason, and no one questioning waste is questioning hygiene. What unsettled Lee was the material itself. Why were items designed to be used for minutes made from petroleum-based plastics that would outlast the tattoo by centuries?

Around the same time, Lee was tattooing Ryan, an entrepreneur who immediately recognized the gap between necessity and default.

What followed wasn’t a polished launch or a rebrand of existing products. It was years of trial and error. Compostable films borrowed from other industries. Biodegradable gloves that still needed to stretch, grip, and hold up through long sessions. Barriers that couldn’t tear, leak, or slip mid-tattoo. Many attempts failed. Some worked better than expected.

That work eventually became Good Judy, a tattoo supply company built around a simple premise: safety and sustainability don’t have to be opposing forces. The product line includes compostable station covers and pen covers designed to meet daily studio demands, along with cactus leather tattoo pillows and sample packs that allow artists to test materials in real working conditions before committing to a full switch.

From the beginning, the founders understood something tattoo artists know well. Intent doesn’t matter if a product doesn’t perform. Sustainability claims had already trained artists to be skeptical. Labels promised biodegradability. Certifications were vague. Proof was often missing.

“We were sold products that claimed to be eco, and when we asked for documentation, it just wasn’t there,” Ryan explains. “That’s when we realized verification had to be part of the mission, not an afterthought.”

Instead of relying on marketing language, the company began working with third-party certifiers, including the Compost Manufacturing Alliance, publishing field test reports that show how materials actually break down. Education became part of the offering, not a footnote.

“We don’t expect artists to just trust us,” Lee says. “Artists question everything. We want people to understand what makes a material compostable or biodegradable, and what that actually means outside of a studio.”

Inside shops, the response has been gradual but telling. Artists who are meticulous about setup, breakdown, and workflow began applying that same scrutiny to materials. The shift, when it happened, wasn’t ideological. It was practical.

“One of the most common things we hear is that the products perform better,” Lee notes. “Once artists realize they’re not giving anything up, the conversation changes.”

Good Judy now ships across the United States from Chicago and is preparing to open a storefront in Toronto designed around access, education, and community. Plans include refill systems, bulk purchasing, and continued investment in reusable tools and hybrid solutions where possible. The founders are also collaborating on ways to improve access to autoclaving and reduce waste beyond barriers alone.

As of January 8, 2026, Good Judy has also launched a month-long customer appreciation sale. The timing reflects the company’s ongoing focus on accessibility, giving artists and shops an opportunity to explore alternative materials without treating sustainability as a premium add-on.

The mission remains intentionally unfinished.

“There’s no single fix,” Ryan says. “Single-use is still required for safety. What we can change is what those materials are made from, how transparent the process is, and where the industry goes next.”

That philosophy extends beyond individual products. It shows up in how money moves through the supply chain and which manufacturers are supported.

“Tattoo supply companies are consumers too,” Ryan adds. “Where we spend our money shapes what gets built.”

Looking ahead, the founders are focused on the parts of tattooing that still hide in plain sight. Bottles. Packaging. Products that have always been replaced without question. New plant-based, home-compostable containers and redesigned disposables that use less material are already in testing.

For Lee, the goal has never been to turn sustainability into a trend.

“Tattooing is already about intention,” they say. “This is just extending that mindset to the tools we use every day.”

In an industry built on permanence, change rarely arrives all at once. Sometimes it starts with a single observation, a moment of discomfort, and the decision to question something everyone else accepts as normal.

Not whether tattooing can exist without disposables, but whether those disposables have to last forever.

More information on Good Judy’s approach, products, and ongoing research can be found at goodjudy.ca.

Leave a Reply